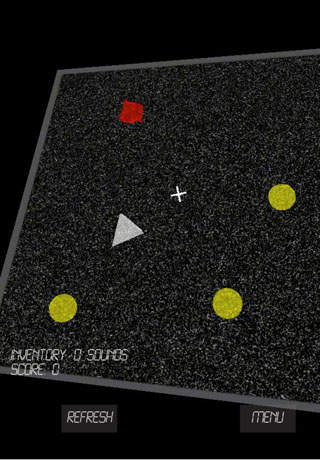

Title: Sound Swallower

Artist: Aaron Oldenburg

Medium: Digital Mobile Game

Sound Swallower creates a composition based on the real world ambient environment. In this game, your goal is to

run and collect fragments of your environment's auditory history before it is erased. Thomas Edison believed that

“sounds may linger as elusive auditory ghosts - physical clutter or memory residue that can be accessed by recording

technology. . . .” (David Toop, Sinister Resonances). The player records at the location of an abstract sound from

the past, and the sound is layered over the recording of the current environment.

The player explores a hidden sonic environment outdoors using their device's GPS and built-in microphone while avoiding the Sound Swallower. This enemy is inspired by Karlheinz Stockhausen’s idea of a device that "would be equipped with hidden microphones to pick up sounds on the streets and a computer to analyze the sounds, create negative wave patterns, and return them to cancel out the original sounds" (Kahn, Noise, Water, Meat).

This is from a series of several experiments in audio-based game design that attempt to expand the expressive vocabulary of games, probing what appears to be under-explored territory in audio games: sonic interaction beyond conventional melody and rhythm games. Broader definitions of music, such as those proposed by John Cage, have not been widely explored in music-based digital games.

What aspects of audio hold potential for game-based simulation? Consider the following descriptions of sounds in the context of actions, environments and visual representations in videogames. David Toop in his book Sinister Resonances compares sound’s properties to those of “perfume or smoke,” stating that “sound’s boundaries lack clarity, spreading in the air as they do or arriving from hidden places.” He points out that sound “implies some degree of insubstantiality and uncertainty, some potential for illusion or deception, some ambiguity of absence or

presence,” and that, "through sound, the boundaries of the physical world are questioned, even threatened or undone by instability.” Sound also has the “ability to stretch across the cut, to meld continuously from one ‘object’ or entity to another.” Sound always arrives at our ears blended, like shadows. Typical games, by contrast, are often about the

manipulation of distinct objects with logical boundaries. Games are often, however, about discovering alternate universes, and so contain the potential to allow players to explore worlds with fluid boundaries and objects that blend or arrive with ambiguous origins, like sound.

Humans cognitively approach sound in ways that we do not engage with our other senses. Could it be that in games, navigating a 3D spatial tactile world is not the best way to move? How about forward and backward through the time of a sound? What choices could the player make as they move, what obstacles overcome? Studying audio

gives game designers new ways to construct (and deconstruct) space and action. Conversely, the 3D spatio-centric worlds of video games give artists who work with audio a space where they can explore goal and conflict-based compositional techniques, giving their audiences the potential to engage and procedurally explore the processes of hearing and listening.